Introduction: The Invisible Seam

If you were born in 1976, you occupy a strange, often invisible seam in modern history. You are technically Generation X, but you arrived too late for the original punk explosion and the profound cynicism of the early 80s recession. Yet, you are decidedly not a Millennial; you experienced an entire childhood and adolescence completely free of the internet, mobile phones, and social media surveillance.

Those born in ’76 are the ultimate “bridge cohort.” They are the youngest people to remember the Cold War as an active, terrifying reality, and the oldest people to have adopted the internet not as a mid-career pivot, but as a foundational tool of their early adulthood.

They don’t talk about this experience because it’s difficult to articulate the feeling of having one foot planted in an analog reality that has completely vanished, and the other in a digital acceleration that has yet to stop. They are the translators. They know how to fix a VCR tracking issue and how to configure a cloud server.

But more than just technological straddlers, the ’76 cohort experienced a unique emotional trajectory. They came of age during a very specific, brief historical window—roughly 1989 to 2001—where it felt like the world had finally gotten its act together. It was a period of intense, almost delusional optimism between the fall of the Berlin Wall and the fall of the Twin Towers.

This article explores that silent journey. It is about growing up preparing for a world that ceased to exist the moment they graduated, and spending adulthood building a new one without a manual.

Part I: The Last Analog Childhood (1976–1988)

To be born in 1976 was to experience the final iteration of a “free-range” childhood. It was a world defined by physical presence and tangible media. If you wanted to see a friend, you rode your bike to their house and knocked on the door. If they weren’t home, you left. There was no way to track them down.

At age ten, in 1986, the ’76er’s worldview was dominated by two towering realities: the threat of nuclear annihilation and the monoculture of linear television. The Cold War wasn’t an abstract concept; it was the backdrop of movies like WarGames and Red Dawn. It was the subtle, pervasive anxiety that the world could end at the push of a button before you finished junior high.

This generation learned patience through technological limitations. They waited for their favorite song to come on the radio so they could hit “record” on their boombox. They waited a week for photos to be developed, having no idea if the pictures were any good. Media was precious because it was scarce. You watched what was on the three or four available channels, or you watched nothing.

This analog foundation instilled a certain kind of resilience—a capacity for boredom and solitude that later generations would find difficult to access. Their brains were wired before the dopamine feedback loops of infinite scrolling existed. They learned to navigate the physical world using paper maps and landmarks, developing an internal compass that didn’t rely on GPS.

Yet, this childhood also felt oddly static. The mid-80s felt like a permanent state of affairs. The geopolitical giants were locked in a stalemate. Culture felt dominated by Boomer nostalgia (The Big Chill era). The idea that the entire geopolitical structure of the planet was about to crumble was unthinkable.

Part II: The Great Exhale and the End of History (1989–1993)

Then, everything changed overnight.

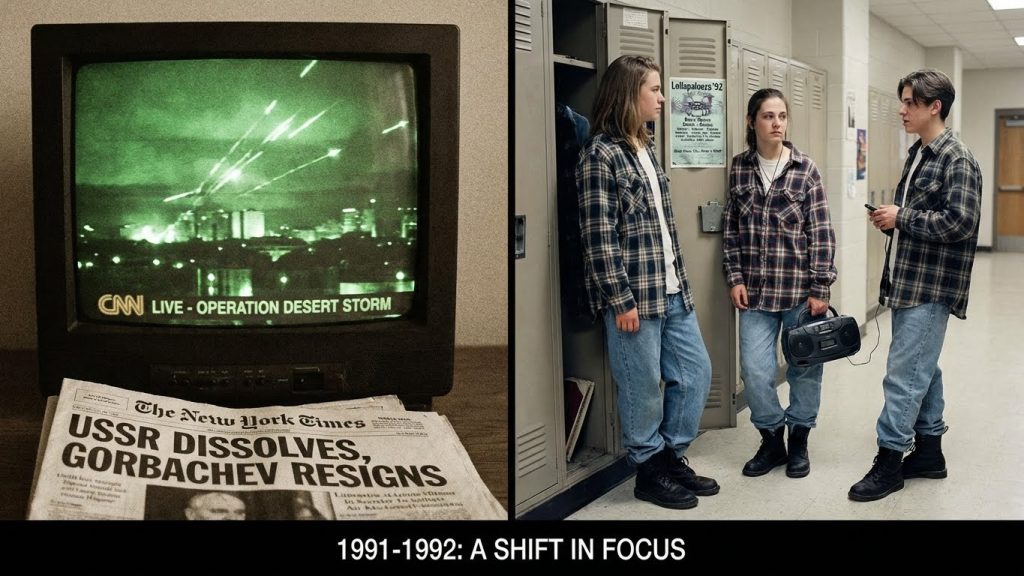

For the cohort born in 1976, their 13th year, 1989, was the pivotal turning point. They entered their teenage years precisely as the Berlin Wall fell.

It is impossible to overstate the psychological impact this had on an impressionable adolescent mind. The existential “Big Bad”—the Soviet Union—didn’t end with a nuclear bang, but with a bureaucratic whimper and David Hasselhoff singing on the rubble.

Suddenly, the defining tension of the 20th century evaporated. Political scientist Francis Fukuyama famously declared “The End of History,” suggesting that liberal democracy and free-market capitalism had won the final ideological battle. For a teenager in the West, this translated into a profound sense of geopolitical exhale. The Doomsday Clock was wound back. The future suddenly looked open, safe, and incredibly promising.

The early 90s, as the ’76ers navigated high school, felt like a victory lap. The economy was recovering from the early 90s recession. Globalization was the exciting new buzzword. The Gulf War, seen through the greenish tint of CNN night-vision, felt less like a global conflict and more like a technological demonstration of Western supremacy, quick and relatively sterile (from a Western media perspective).

This cohort went through high school during a unique historical “holiday.” They didn’t have the Vietnam draft looming over them like the Boomers, nor the imminent climate catastrophe and economic precarity that shadows Gen Z. They were promised that if they followed the rules—went to college, got a degree—the system would reward them with a prosperous, stable life in a peaceful world.

They had no reason to doubt it.

Part III: The Grunge Pivot and the Digital Dawn (1994–1997)

The Class of 1994. If you were born in 1976, this was your graduation year. It was a year defined by two massive cultural tectonic shifts that would shape your adulthood.

The first was the suicide of Kurt Cobain in April 1994, just months before graduation. Cobain was the reluctant avatar of the older Gen X’s disaffection. His death felt like the closing of a door on the pure, cynical, slacker ethos. For the ’76er, standing on the precipice of adulthood, grunge had already peaked. The genuine angst was being packaged and sold back to them in Hot Topic suburban malls. They bought the flannel, but they couldn’t quite commit to the nihilism because, frankly, their prospects looked too good.

The second shift was the arrival of the internet as a consumer reality.

Throughout their college years (roughly ’94–’98), the internet transformed from a rumor into a utility. They were the generation that first encountered the “World Wide Web” in university computer labs on monochrome terminals. They were the first to get email addresses, usually complex strings of university-assigned letters and numbers.

They experienced the internet when it was loud. The screeching, grinding digital handshake of a 56k modem was the soundtrack of their late nights.

Crucially, they adopted the internet when it was still a place of utopian potential, before it became a surveillance capitalist marketplace. It was a wild frontier of GeoCities pages, IRC chat rooms, and the thrilling discovery of information that wasn’t curated by three TV networks. It felt subversive, democratizing, and intensely personal. You didn’t “log on” to check an algorithm; you logged on to explore a new territory.

This cohort learned to type on physical keyboards, developing muscle memory for shortcuts and command lines. They learned HTML because if you wanted a presence online, you had to build it yourself. They were the digital pioneers who were old enough to understand the structures of the old world, but young enough to intuitively grasp the mechanics of the new one.

Part IV: The Dot-Com Mirage and the Ethics of Selling Out (1998–2000)

The ’76 cohort entered the full-time workforce at the absolute apex of the Dot-Com Boom. This timing was everything.

They graduated college and stepped onto a moving walkway of insane economic optimism. The traditional rules of paying your dues, climbing the corporate ladder for twenty years, and waiting for a gold watch seemed obsolete overnight.

Suddenly, 23-year-olds were being offered six-figure salaries (on paper, largely in stock options) to be “webmasters” or “content strategists” at companies that had no revenue but massive valuations. The workplace culture shifted radically. Suits and ties were out; khakis, polo shirts, and office foosball tables were in.

For a generation raised on a mild Gen X skepticism of “The Man,” this presented a complex ethical dilemma. Was taking a high-paying tech job “selling out,” or was it a subversive act to hack the system and get rich quick without turning into your boring dad?

Many chose the latter interpretation. They threw themselves into the “New Economy.” They worked insane hours, fueled by free office soda and the belief that they were building a new paradigm. The zeitgeist told them that the business cycle had been defeated by technology. Recession was a thing of the past.

This was the peak of the historical hallucination. A person born in 1976, aged 23 in 1999, stood at the summit of Western triumphalism. The world was peaceful, the economy was unstoppable, and technology was a benevolent force opening unlimited doors.

They were preparing to inherit the earth.

Part V: The Double Trauma—The Shattering of Illusions (2001 & 2008)

The hangover for the ’76 cohort was brutal, and it came in two distinct waves that dismantled their foundational assumptions about the world.

The first wave was the Dot-Com crash of 2000-2001, followed immediately by 9/11.

The economic crash proved that the “New Economy” was just the old economy on steroids. The paper millionaire status of many ’76ers evaporated overnight. The cool startup jobs vanished, and they found themselves competing for traditional, boring jobs, burdened by the realization that they were not economic alchemists.

Then came September 11, 2001. The ’76 cohort was 25 years old. The “holiday from history” that had begun when they were 13 officially ended. The geopolitical safety they had taken for granted was revealed to be an illusion. The world wasn’t post-conflict; the conflicts had just been festering beneath the surface.

This was a profound psychological whiplash. They had gone from Cold War anxiety in childhood, to end-of-history euphoria in adolescence, to a sudden, terrifying clash of civilizations in early adulthood.

They put their heads down. They assimilated the older Gen X cynicism they had previously kept at arm’s length. They worked hard, started families, bought homes (often at inflated prices), and tried to regain their footing.

Then came the second wave: The Great Recession of 2008.

At age 32, just as this cohort should have been entering their prime earning years and building real equity, the floor fell out again. The housing market collapsed. Retirement accounts were halved. The corporate ladder they had grudgingly decided to climb suddenly had its middle rungs removed.

This second trauma was devastating because it punished them for following the rules. They had done what they were told—bought the house, invested in the 401k—and the system failed them anyway.

This is the core of the unspoken experience of the ’76er. They were promised the easiest ride in history, only to have the rug pulled out from under them twice in their critical developmental years. They were primed for optimism, then force-fed reality.

Conclusion: The Quiet Resilience of the Hinge Generation

Today, people born in 1976 are approaching their late 40s. They are the exhausted, squeezed middle management of modern society. They are caring for aging Boomer parents who still don’t quite understand how email attachments work, while raising Gen Z children who view the world through a prism of crisis and digital ubiquity that the ’76er finds both awe-inspiring and terrifying.

They don’t talk about their unique historical path because it feels self-indulgent compared to the struggles of others. They don’t have the collective volume of the Boomers or the digital megaphone of the Millennials.

But their experience shaped a unique temperament. They possess a hybridized worldview that is essential right now. They have the analog groundedness to know that not everything on a screen is real, matched with the digital fluency to navigate the systems that run the world.

They are deeply skeptical of utopian promises, having seen how quickly “New Economies” and “New World Orders” collapse. Yet, they lack the paralyzing nihilism that sometimes afflicts older Gen X or the intense anxiety of younger generations. They remember a time when things felt okay, which gives them a secret reservoir of hope, even if it’s buried deep under layers of acquired cynicism.

They are the ones currently keeping the legacy systems running while trying to integrate the new AI overlords. They are the generation that knows how to restart the router, both literally and metaphorically.

The person born in 1976 is the quiet survivor of historical whiplash. They were the last to have a childhood where they could truly disappear, and the first to enter an adulthood where disappearing became impossible. They are the bridge over the chasm between the 20th and 21st centuries, a bridge built on the fly, often rickety, but surprisingly durable. And even if they don’t talk about it, that act of bridging shaped everything they became.